In this post, we will explore the mathematics behind GANs. This serves as an introductory post before I demonstrate and engage in practical work on using DCGAN to generate synthetic images of deep space objects in the next post. The intention behind this post is to deepen my understanding of GANs and their mathematical framework, which greatly interests me. It is one of the reasons why I love AI, due to its extensive mathematical applications.

What is GAN ?

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) refer to a family of generative models that seek to discover the underlying distribution behind a certain data generating process, enabling the generation of new data from that same distribution. GANs have revolutionized deep learning over the past decade since the release of the first version of GAN in 2014 by Ian Goodfellow et al. Before GANs, the state-of-the-art in image generation was primarily dominated by techniques like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs). However, GANs quickly emerged as a powerful alternative, that have unique capabilities in generating images. Although recent advancements in generative modeling have introduced techniques like diffusion models and transformers, GANs still a cornerstone technology in image generation and have continued to evolve with new architectures and applications.

GAN Theoretical Overview

This theoretical overview is based on the original paper by (Goodfellow et al. 2014) titled ‘Generative Adversarial Nets’. Additionally, insights were drawn from Jake Tae’s writing (Tae 2020) and the paper by (Wang 2020) titled ‘A Mathematical Introduction to Generative Adversarial Nets’. Without these references, understanding GAN would have been challenging.

Loss Function

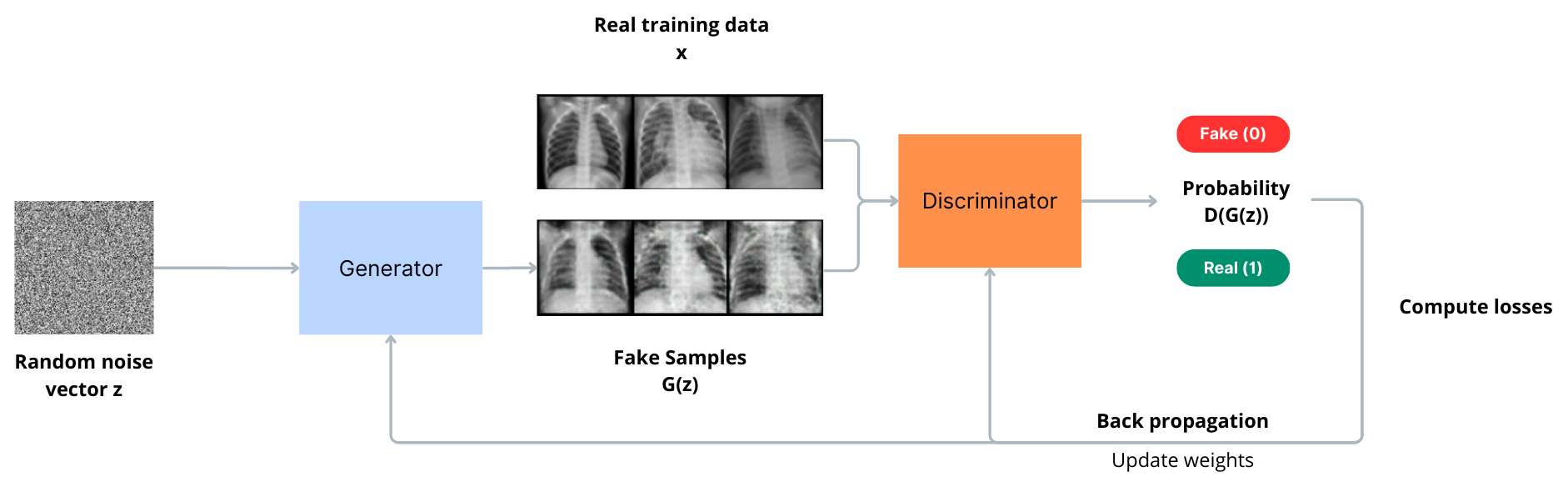

GAN consists of two distinct models: a generative model (G) that captures the data distribution and a discriminative model (D) that estimates the probability that a sample came from the training data rather than from G. The generator produces images that resemble the training images or “fake” images. During training, the generator continuously tries to outsmart the discriminator by generating better and better fakes, while the discriminator strives to become a better detective and accurately classify real and fake images. As discriminator learns to discriminate between the two, it provides feedback to the generator about the quality of its generated samples. This is why the term “adversarial” is used here. Equilibrium is achieved when the generator produces perfect fakes that closely resemble samples from the training data, and the discriminator is left guessing at a 50% confidence level whether the generator output is real. Thus, there will be a loss function to evaluate the performance of each of the models.

Notation

Defining notation that we will be using in this post: \[ \begin{aligned} & x \ \text{: Real data} \\ & z \ \text{: Latent space vector sampled from a standard normal distribution} \\ & G(z) \ \text{: Fake data} \\ & D(x) \ \text{: Discriminator's evaluation of real data} \\ & D(G(x)) \ \text{: Discriminator's evaluation of fake data} \\ & \text{Error}(a,b) \ \text{: Error between a and b} \\ \end{aligned} \]

Binary Cross Entropy

A common loss function that is used in binary classification problems is binary cross entropy. This mathematically described as: \[ \begin{aligned} & H(p,q) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{(x)}}[- \log q (x)] \end{aligned} \tag{1}\]

For a classification task, the random variable is discrete. Therefore, the Equation 1 can be expressed as a summation: \[ \begin{aligned} & H(p,q) = -\sum_{x \in \chi}p(x)\log q (x) \end{aligned} \tag{2}\]

In the context of binary classification, we have two possible labels: 0 and 1. Therefore, the sum in the above expression would involve only two terms, corresponding to these two labels.

Let’s denote the true label as \(y\) and the predicted probability for class 1 as \(\hat{y}\). Thus, we have:

- For a real input, \(y = 1\). Substituting this into the binary cross-entropy loss function gives the following loss value:

\[ \begin{aligned} & H(y,\hat{y}) = - (y \log(\hat{y}) + (1 - y) \log(1 - \hat{y})) \\ & H(1,\hat{y}) = - y \log(\hat{y}) \end{aligned} \tag{3}\]

- Similarly, for a fake input, \(y = 0\). Substituting this into the binary cross-entropy loss function gives the following loss value:

\[ \begin{aligned} & H(y,\hat{y}) = - (y \log(\hat{y}) + (1 - y) \log(1 - \hat{y})) \\ & H(0,\hat{y}) = (1 - y) \log(1 - \hat{y}) \end{aligned} \tag{4}\]

Therefore, we can rewrite the expression for the binary cross-entropy loss as:

\[ \begin{aligned} & H(y,\hat{y}) = -\sum y\log (\hat{y}) + (1-y)\log (1-\hat{y}) \end{aligned} \]

The Discriminator

The discriminator task is to correctly label generated images as false and empirical data points as true. We might consider the loss function of the discriminator: \[ \begin{aligned} & L_{D} = \text{Error}(D(x),1) + \text{Error}(D(G(z)),0) \end{aligned} \tag{5}\]

Applying Equation 2 into Equation 5, the expression will be written as:

\[ \begin{aligned} & L_{D} = -\sum_{x \in \chi, z \in \zeta} \log(D(x)) + \log(1-D(G(z))) \end{aligned} \tag{6}\]

The Generator

The generator task is to confuse the discriminator as much as possible such that it mislabels generated images as being true. The loss function for the generator is written as:

\[ \begin{aligned} & L_{G} = \text{Error}(D(G(z)),1) \end{aligned} \tag{7}\]

Because loss function is something we want to minimize, in the case of the generator, it should minimize the difference between, the label for true data and the discriminator’s evaluation of the generated fake data.

Applying Equation 2 into Equation 7, the expression will be written as:

\[ \begin{aligned} & L_{G} = -\sum_{x \in \zeta} \log(D(G(z))) \end{aligned} \tag{8}\]

Now, we have two loss functions to train both the generator and the discriminator, which work together. If \(D(G(z))\) is close to 1 when the discriminator evaluates the generator’s output, then the generator’s loss is small. This occurs because a discriminator output of 1 indicates that the discriminator is highly confident that the generated image is real, hence the generator’s loss is minimized. This aligns with our objective for the generator’s loss function.

Model Optimization

Model optimization is the process of using mathematical and computational methods to solve optimization problems. For our case, the goal is to find parameters for both the generator and the discriminator such that the loss functions are optimized. In practical terms, this involves training the models and minimizing the loss function.

Training GAN

In the training of a GAN, we aim to optimize both the generator \(G\) and the discriminator \(D\) simultaneously. To do this, we need to combine the individual loss functions of the generator and discriminator into a single objective function that captures the overall performance of the GAN. Combining both the loss functions Equation 6 and Equation 8 will give us a objective function which is defined as a function of \(G\) and \(D\). This objective function is expressed as:

\[ \begin{aligned} & V(G, D) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[ \log(D(x))] + \mathbb{E}_{z \sim p_z}[\log(1 - D(G(z)))] \end{aligned} \tag{9}\]

This objective function measures the effectiveness of the discriminator in distinguishing real data from generated data produced by the generator. Here, \(x\) represents real data samples drawn from the true data distribution \(p_{data}\) and \(z\) represents random noise vectors sampled from a distribution \(p_{z}\).

Because we are interested in the distribution that is modeled by the generator, we will rewrite the Equation 9 by defining a new variable \(y=G(z)\). This makes it easier to understand that the GAN objective function is terms of the generated samples rather than the latent vector: \[ \begin{aligned} & V(G, D) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log(D(x))] + \mathbb{E}_{y \sim p_g}[\log(1 - D(y))] \end{aligned} \tag{10}\]

In cases where the dimensionality of the output space \((y)\) is higher than the dimensionality of the input space \((z)\), we can represent Equation 10 as an integral over the input space:

\[ \begin{aligned} & V(G, D) = \int_{x \in \chi} p_{\text{data}}(x) \log(D(x)) + p_g(x) \log(1 - D(x)) \, dx \end{aligned} \]

In the Equation 10, the first term represents the expected value of the logarithm of the discriminator’s output when fed with real data \(x\) sampled from the true data distribution \(p_{\text{data}}(x)\) and the second term represents the expected value of the logarithm of \(\log(1 - D(x))\) when \(x\) is sampled from the generator’s distribution \(p_g(x)\) (Read more about Expectation Value).

The optimization of the generator and discriminator involves a minimax game, where the generator tries to minimize its loss while the discriminator tries to maximize its own. In other words:

\[ \begin{aligned} & \min_G \max_D V(D, G) \end{aligned} \tag{11}\]

Training Discriminator

The task of the discriminator is to maximize this objective function. Remember, the discriminator’s role in the GAN framework is to accurately differentiate between real and generated samples. By maximizing \(V(G,D)\), we ensure that the discriminator is trained to assign high probabilities to real samples and low probabilities to generated samples. This encourages the generator to produce samples that are increasingly similar to real data, ultimately improving the quality of the generated output. We can do the partial derivative of \(V(G,D)\) with respect to \(D(x)\) to find the optimal value of the discriminator denoted as \(D_{Optimal}(x)\). The result of this derivative yields the expression: \[ \begin{aligned} D_{\text{Optimal}}(x) = \frac{p_{\text{data}}(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x) + p_g(x)} \end{aligned} \tag{12}\]

This equation represents the optimal discriminator for a given input \(x\). It calculates the probability that the input \(x\) belongs to the real data distribution \(p_{\text{data}}(x)\) relative to the sum of probabilities from both the real and generated data distributions.

To explain the Equation 12 intuitively, \(D_{\text{Optimal}}(x)\) assigns a value close to 1 when the sample \(x\) is highly likely to come from the real data distribution, and a value close to 0 when it is more likely to come from the generator’s distribution. This ensures that the discriminator effectively distinguishes between real and generated samples.

Training Generator

Training the generator, we assume the discriminator to be fixed. Substitute the equation Equation 12 into our objective function Equation 9: \[ \begin{aligned} & V(G, D_{\text{Optimal}}) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log(D_{\text{Optimal}}(x))] + \mathbb{E}_{y \sim p_g}[\log(1 - D_{\text{Optimal}}(x))] \\ & V(G, D_{\text{Optimal}}) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log{\frac{p_{\text{data}}(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x) + p_g(x)}}] + \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{g}}}[\log{\frac{p_{\text{g}}(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x) + p_g(x)}}] \end{aligned} \tag{13}\]

The equation eventually is expressed as a Jensen-Shannon divergence: \[ \begin{aligned} & V(G,D^*) = -\log 4 + 2 \cdot D_{JS}(p_{\text{data}} \| p_g) \end{aligned} \tag{14}\]

This occurs through a process after the substitution with clever tricks to interpret the expectations as Kullback-Leibler divergence, derived from the properties of logarithms in the equation.

Finally, we can interpret Equation 14 as follows: during training of the generator, the goal is to minimize the objective function \(V(G,D)\) such that we want the Jensen-Shannon divergence between the distribution of the data and the distribution of the generated samples to be as small as possible. The part here, \(p_{\text{data}} \| p_g\), implies that the distributions \(p_{g}\) and \(p_{data}\) should be as close to each other as possible. Therefore, the optimal generator \(G\) is the one that able to mimic \(p_{data}\) from the generated sample distribution \(p_{g}\).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this post serves as a brief overview of the mathematics behind GANs, providing a solid starting point for exploring into this fascinating topic. It is important to note that the world of GANs is vast, with numerous variants with distinctive architectures and mathematical frameworks. While this overview covers the fundamentals, exploring various GAN variants and their underlying mathematics can offer deeper insights and opportunities for further learning.